I’m making a point of examining the great surviving tragedies of Ancient Greece. The time was right, I knew, when a Signet Classics edition of Euripides: Ten Plays looked at me invitingly from a shelf in the Sofia Airport bookstore this January. It’s a wonderful pocket edition, and it set me back by three euro. My piece of advice? Never miss out on a brand new book full of Ancient Greek goodness for this low a price.

In Medea, the tragic could not be of a more personal nature. This is a tale of a woman scorned, a wife betrayed by the father of her children, for whom she’s spilled the blood of countrymen and kin alike. Medea, child of king Aeëtes of Colchis and granddaughter of Circe, grew up in the territory of present-day Georgia. The easternmost shores of the Black Sea were, to the Hellenistic people, a “wild place” (Paul Roche, Introduction to Medea). Though she bears the blood of the sun god Helios, she is foreign to the inner world of Ancient Greece.

Having taken with Jason and his Argonauts, and aided the hero in his quest, Medea comes to the Hellenistic world proper a barbarian princess. Having butchered her brother and thrown the scraps of his corpse overboard to dissuade Aeëtes from pursuing the Argonauts, she has paid the blood price of loving the hero, Jason:

How dare they do to me what they have done!

p.342, Euripides, Ten Plays, Signet Classics

O my father, my country, the land I abandoned,

Flagrantly killing my brother!

Her rewards seem every inch worth this first blood sacrifice – she is married to the hero, and bears him children, two boys, no doubt a source of pride for any father. At the prologue of the play, the Nurse says about Medea’s role as a wife:

exile though she came

p. 337

and been in everything Jason’s perfect foil–

in marriage that saving thing:

a woman who does not go against her man.

What, to a hero’s ambition and thirst for riches, is a wife who can only offer “in everything [a] perfect foil*”? Jason’s eventual betrayal is designed to further his position – through marriage to princess Glauce of Corinth, he becomes the de facto inheritor of the great Greek kingdom. The beautiful young bride does not hurt, either: “This father does not love his sons. He loves his new wedding bed.”(340)

This is where Euripides’ tragedy picks up at, with Medea furious at the betrayal: “Don’t approach. Beware. Watch out || For her savage mood, destructive spleen; || Yes, and her implaccable will.”(340). The depth of this betrayal has driven her mad, or perhaps the need for recompense has. Looking at her children, hers are the “eyes of a mad bull.” (340)

Soon after, the ruler of Corinth, King Creon himself, comes to her doorstep to order her and her sons banished from the kingdom on pain of death. His reason is “Fear…|| I’m afraid you’ll deal my child some lethal blow || … You are a woman of some knowledge || Versed in many unsavory arts.” (346) Medea time and again attempts to earn herself some small respite and eventually wearing him down and earning herself until the following dawn. It is a decision that will cost Creon, as he suspects when he at last takes pity on her:

My soul is not tyrannical enough.

349

My heart has often let me down . . .

So now, Medea

Though I know I take a false step:

have it your own way.

Creon’s hope that a day won’t be enough for the savage sorceress to perpetrate her ill intent against his daughter is foolhardy. Medea says as much once he leaves, in a speech I can only describe as bordering on the gleefuly wicked:

Friends,

350

I can think of several ways to bring their death about.

Which one shall I choose?

Shall I set their house of honeymoon alight,

or creep into the nuptial bower

and plunge a sharp knife through their innards?

…

No, there is a surer way,

one more direct;

for which I have a natural bent:

death by poison.

Yes, that is it.

Perhaps this is one of those main sources from whom the notion of poison as a woman’s weapon comes from? Certainly, it would make sense, particularly with what Medea tells herself at the end of this lengthy monologue: “Besides, you are a woman: || feeble when it comes to the sublime || marvelously inventive over crime.” (351) It’s a fascinating monologue this early on, one that shows at once the hurt of betrayal, the impish delight at the prospect of vengeance and the marginalised identity of Medea as a woman. I’m partial to these four lines in particular:

See how you are being treated

laughed at by the seed of Sisyphus and Jason:

you, the daughter of a king

and scion of the Sun.

How fucking good is that?! See the wounded pride, see how it urges her on, forces her hand to action like a thorn embedded deep in the heart of a wound. When Jason comes to try and persuade Medea to leave without creating any trouble, it’s like pouring gasoline on that self-same wound.

The scene, in the second episode of the play, is the first thing that’ll come to me whenever I think of gaslighting from now on. Jason explains:

Yet in spite of everything,

353

and patient to the last with someone I am fond of,

I come, Medea, to do what I can to help.

This is unusual cruelty, masked as benevolence. Before these words, Jason blames Medea for her words, tries to shame her, even – but she will neither be shamed or cowed by this oath-breaker:

Monster —

353

an epiteth too good for you.

…

This is not courage.

This is not being brave:

to look a victim in the eye whom you’ve betrayed

–somebody you loved–

this is a disease and the foulest that a man can have.

But hypocrisy is not so easily cured. Jason, who at one point claims that Medea’s sacrifices are far less compared to what their marriage has given her, eventually takes his leave, having done nothing so much as rekindling Medea’s fury to new heights.

She concocts her plan – the exact way in which she will take the life of Jason’s new bride. But this is too small a price to pay – and here, finally, is revealed the full depth of Medea’s severity:

But now, my whole tone changes:

365

a sob of pain for the next thing I must do.

I kill my sons–my own–

no one shall snatch them from me.

And when I have desolated Jason’s house beyond recall,

I shall escape from here,

fly from the murder of my little ones,

my mission done.

It is an unnatural act, a mother killing her children – yet Medea, in her savagery and her connection to the sun god Helios**, is bound to laws different and more ancient than those of the Ancient Greeks. Natural laws, what professor Daniel N. Pederson calls in his Great Ideas of Philosophy the law of revenge, “when the chthonic gods of the earth held sway…and the pleadings of the heart trump the demands of rationality.” Passion in this extremity is madness to the Ancient Greeks, and to us. To Medea, it is a power she cannot contest. It’s in her blood; the same force that bid her hack her brother to pieces for her lover now sees her commit an even more horrendous act to punish Jason – and, in a twisted way, reclaim her children. I repeat, again: “I kill my sons–my own– || no one shall snatch them from me.”

Medea, then, is aware of the personal cost of vengeance, and willing to pay it. Here is a woman capable of ruthlessness and savagery unimaginable to the Greeks, first stealing the lives of Jason’s new bride Glauce, and of her father Creon (the same Creon of Antigone fame), through deception worthy of the granddaughter of the sea witch Circe. Then, when the time comes to act, Medea has a moment of pure reflection:

The evil that I do, I understand full well.

But a passion drives me greater than my will.

Passion is the curse of man: it wreaks the greatest ill.

One of the greatest tragedies of this play is that this realization changes nothing. Medea goes through with it, her vengeance complete. She stays in Corinth just long enough to see Jason come to grips with her vengeance before flying off on the chariot of Helios, pulled by a pair of dragons, denying the father of their dead children even the last goodbye that comes with burying them. The play closes with the Chorus of Athenian women questioning the will of Zeus, wondering why the Olympians have willed this terrible thing to happen, as a disconsolate Jason walks away.

Medea is one of the tragedies of Ancient Greece in which a woman is imbued with the autonomous power to take her destiny in her own hands and deliver blow after blow to the one that has so abused her. It’s more than just a tale of vengeance in the face of infidelity. Medea doesn’t speak for herself alone – her voice is often the voice of the silent masses of women wronged and oppressed by men:

Of all creatures that can feel and think,

p. 344-345

we women are the worst treated things alive.

To begin with,

we bid the highest price in dowries

just to buy some man

to be dictator of our bodies.

How that compounds the wrong!

Hers is an extreme response brought about by the mute suffering of the many before her, a shout of warning and protest in the face of a time in which women are forced into what Pederson calls “a position of reclusive subservience.” It reflects the understanding of the Greek tragedians about the destructive powers of eros, erotic love; but it offers us also a different reading, one which seems not as alien as it first might.

Thanks for reading my essay! You should, without a doubt, read Medea. Me, I think I’ll tackle The Bacchae next!

*I wonder if the notion of the wife as her husband’s perfect foil is drawn out from the Ancient Greek and/or Platonic notion of man and woman as constituting one whole?

**Though I say “god,” Helios is of the older generation of pre-Olympian gods, the titans.

It’s really interesting reading about Medea after having just finished Circe; Medea certainly played a minor role in that book, so it’s really cool that when talking about myth there are all these stories for those “minor characters” (depending whose story we’re focusing on lol).

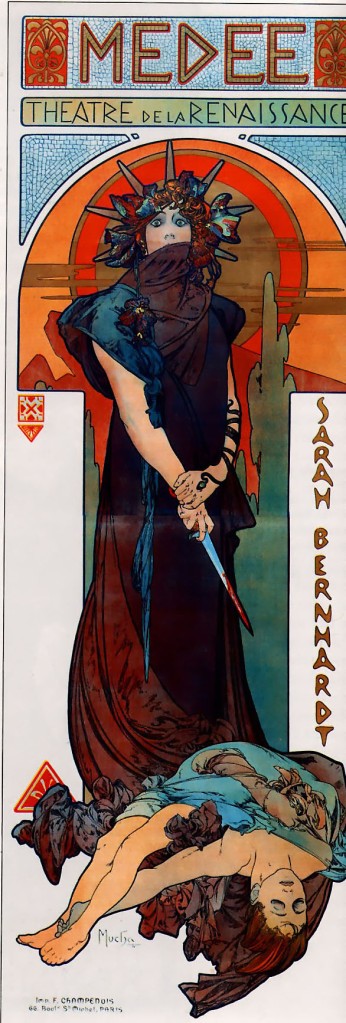

I also really love the art you’ve included in this post! Were these pieces included/referenced in the Signet edition, or are they part of your love for good art?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found the images with help from Google, Amy. I didn’t recall Medea in Circe, actually, guess I’ve forgotten her!

LikeLike

She appeared like once and then was mentioned later like once…but I literally just read it; give me a week and I’ll forget 😂

LikeLiked by 1 person